Well, it’s true that I don’t know even a quarter of what a real cane producer does. But what I do know, I can substantiate with engineering principles and my beginnings were founded on the advice of machine-shop tool maker (my late brother, God rest his soul) who fixed and calibrated machines that built engine parts for air-craft used in the roughest manoeuvres! Also, information on gouging is very hard to find, so by laying out here what I know, I hope to be of service to advanced reed-makers who need something to start their adventure with gouging.

For a more detailed discussion, check-out this thread on the Oboe BBoard.

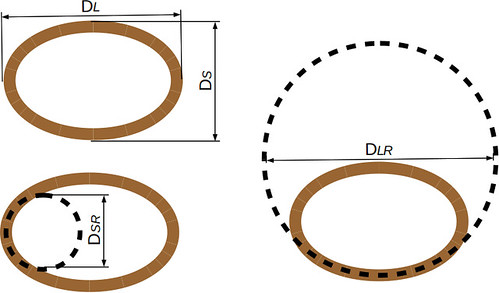

In my last blog post, I talked about how measuring the diameter can be misleading and the arc is more important than the diameter. This picture shows (top left) how using a micrometer or calliper or most diameter-rulers will measure what we think are the long diameter (DL) and short diameter (DS). But in reality, the real short diameter (DSR) is actually smaller and the real long diameter (DLR) is actually longer. Using a radius gage solves this problem by measuring the actual arc.

In my last blog post, I talked about how measuring the diameter can be misleading and the arc is more important than the diameter. This picture shows (top left) how using a micrometer or calliper or most diameter-rulers will measure what we think are the long diameter (DL) and short diameter (DS). But in reality, the real short diameter (DSR) is actually smaller and the real long diameter (DLR) is actually longer. Using a radius gage solves this problem by measuring the actual arc.This means that, when you buy cane, you have to be sure that your supplier is measuring the same way (with the same tool) you are! But that only matters, when you buy gouged or shaped cane, because when you buy canon (tube) cane, the measurement range is really just an average of what you can expect. After a piece of cane has been gouged, it is virtually useless to do any kind of measurement of diameter or arc, because the actual tensions in the cane grains pull the sides together a little bit: a curl results and the arc has changed. Diameter measurements, then, must be done at before splitting or before gouging and then the cane must be stored in well marked containers.

Pitfalls of the scientific method.

Personally, I think we tend to over-value the importance of any given measurement. Cane is a plant, not a high density polymer! Diameter is one issue, but the thickness of the cane wall must certainly mean something too! There is also age, density, health and many other factors, not even considering the staple being used, the shape and the weather (when making and when playing)!Do keep a record of measurements, binding, shaping and scraping characteristics (not to mention observations on cane quality), but don’t draw conclusions based on less than 5 to 10 reeds and don’t immediately discard cane or a reed you’re working on just you think one or two measurements were missed. I have had amazing reeds with almost all descriptions of cane and often the best “setup” has produced reeds that just went to the garbage.

Modern science works by attempting to isolate a single variable and see the effects when that variable changes: then the study is performed again by isolating another variable. This assumes that a model can be built from those different variable changes: a tenuous assumption at best which most serious scientists will hold as difficult. Proof: weather prediction is probably the most sophisticated and intensely researched multivariate model – how well does that work?

For making oboe reeds, this means that it might be best to just keep all the cane (throw away what we know from experience just won't work) and learn to adapt our technique to get as good as possible a reed from whatever piece of cane we get.

Gouging means correct measuring.

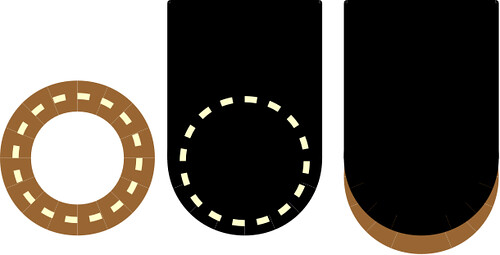

A serious reed maker should begin shaping cane as soon as possible. Jay Light wrote something to the effect of: "an intelligent chimpanzee can shape cane". But one of the really important elements of quality control in cane, especially for the oboe, is the gouging: the thickness and inner curve of the cane used. This is much more difficult than shaping, unless you know a vendor of gouging machines that will adjust your setup. The equipment is VERY expensive and there are different ways to gouge the cane. Overall, if you can get a good supplier of gouged cane, I recommend leaving it at that. But here's some theory for curiosity's sake!As soon as we start gouging, we need ultra-precise measuring tools. The micrometer is a dial (or digital) comparator mounted so it points to another pin, either perpendicular or inline. The perpendicular pin is necessary for the measuring of finished reeds, but the inline type is better for gouging because of the risk of incorrect angle.

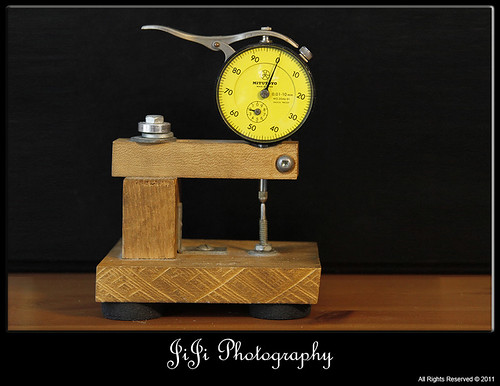

In my last blog post, I showed pictures of a home-made wood base for chopping pre-gouged cane. I also made a base for my dial indicator ($35, at the time) because I could not afford the full micrometer ($250, at the time). I made the base of wood and the other point with a screw that I filed into a ball point using metal files and fine sharpening stones. I don't recommend anyone else do this or even use my micrometer, because any displacement of the arm will cause incorrect readings.

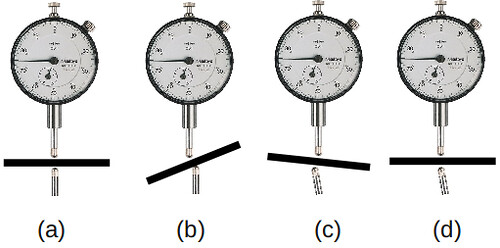

In the image above (a) and (d) are correct because the ball-points of each are in line: this is evidenced when a piece of flat metal is perfectly perpendicular to the measuring prod. Otherwise, when there is displacement the read measurement is longer than the real thickness as proven by the equation familiar to everyone who did trigonometry:

realThickness = | measuredHeight X sin( angle )|

Perpendicular means sin( angle ) = 1, so no flaw in the measurement. Displacement can happen front to back and side to side, so when it gets maladjusted, it can take 15 minutes to get it right again!Now, The blade is shaped to have roughly the same diameter as the cane tube. Because it is elevated from the base, when gouging, it will make the sides thinner than the center: this is usually what we want.

In fact, most of us want a much thicker center compared to the sides for better tuning stability and warmer sound. Thinner sides also help the reed close, saving on endurance. Because my machine is old and beaten up, I do this myself by reshaping the curve of the blade.

In fact, most of us want a much thicker center compared to the sides for better tuning stability and warmer sound. Thinner sides also help the reed close, saving on endurance. Because my machine is old and beaten up, I do this myself by reshaping the curve of the blade. Here is the blog page of one well respected American Scrape reed maker and vendor on his adventure learning how to make (and shape) gouger blades. This should be enough to dissuade anyone (even me) from attempting it! A lot of experience and skill is required, and the appropriate tools are not a luxury, they are absolutely required.

There is also another technique called "double-radius" whereby the blade is a little off-center. When the cane is flipped around in the machine, the offset automatically goes to the other side of the cane. This causes 2 grooves to occur in the cane producing a stronger center. In the picture, the 2 green blades illustrate how flipping the cane changes where the blade cuts the cane. Not all machines do this (mine does but I don't dare attempt it with its difficult setting screws), so sometimes reshaping the blade is the only way to get a thicker center <=> thinner sides.

Different mechanisms exist to control the final thickness of the cane: the height adjustment of the blade assembly (plane) is stopped by a roller. My gouger uses a double-wedge guide: pull the bottom wedge to the left to make the cane thinner and to the right for thicker cane. There are pitfalls with this, most notably the difficulty in fine adjustment, but also it lacks any guarantee of parallelism with the cane bed.

If you choose to buy a gouging machine, I HIGHLY recommend you get one with the following characteristics:

- First choice: one-piece construction with fewest adjustments possible!

- Second choice: exchangeable beds so you can use most of the machine for oboe and English Horn.

- In all cases: height adjustment should be on the wheel, not the guide... keep away from those 2ble wedge height adjusters (like mine)

6 comments:

Nice post, Robin!

It's good for us oboists to know the "science" behind reed making. You tackled here the step that I think requires most of the science: the gouging. I unfortunately don't have a gounging machine, so I depend on whatever the vendors provide me. I have to say, though, that because of that, I have learned to make almost all kinds of cane to speak, and many times even play well. This does affect consistency, but as you mentioned, there are so many variables at stake, that I decided to let the cane speak with its own voice. In the end, however, nothing beats being able to go through the whole process by yourself if you have the tools.

In the link to the Oboe BBoard thread, one contributor does a quick financial analysis to show that the $2500 or so you'll spend on new equipment (cheaper if you can get used) plus whatever it costs in cane over the years is still far less than buying pre-gouged cane.... but you have to do need the money up front.

If you get your equipment from a vendor that really knows the stuff (in the U.S.A., there are several - I should link their sites here), then you can be assured a good end result with few worries: just mail it periodically for sharpening and adjusting.

Dan Ross sells a nifty little gadget made by Starrett, a 7/32" "duck" as he calls it, which will measure cane at about 11 mm in diameter. Helps in deciding where to split the tube cane for optimum fit in the gouger bed. It works beautifully on Dan's oboe cane gouger, set up to gouge 11 mm diameter tube cane, which constitutes most of a pound of 10.5-11.0 mm diameter, at least in my experience.

Does it test for flatness? Cane, being a soft material, is capable of bending in or out to fit the bed. Flatness, however, affects the final reed's opening. Eye-ball comparing is inexpensive and fully effective.

Hi Robin,

No, only diameter. You still have to test for flatness/twisting (flattening) potential by placing the split pieces on a flat surface & scoping them out at eye level.

http://rosswoodwind.com/supplies/radius%20gauge%201.htm

You're quite right. This is a simpler (and cheaper) version of my tool at the top of the post. Starrett is an industry leader in measuring tools.

Thanks for the link: I didnt't know this place.

Post a Comment