It might be interesting to explain what all the screws do on the machine, but if you have to ask the question, buy a one-piece construction machine that requires no calibrating! There is also a no adjustment machine called a ”Crank Gouger” only available at Innoledy. There is a thread on this machine at the Oboe BBoard. Personally – apart from preferring to save my money for an oboe d’amore – I like the idea of being able to change the shape of my blade, which I think is impossible on those machines.

Calibrating the machine – general principles.

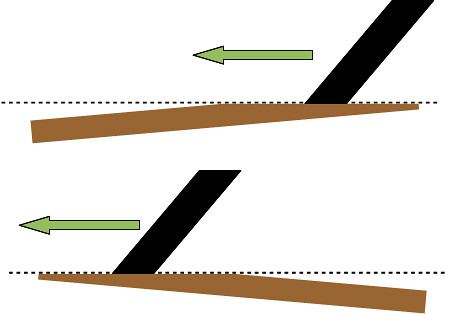

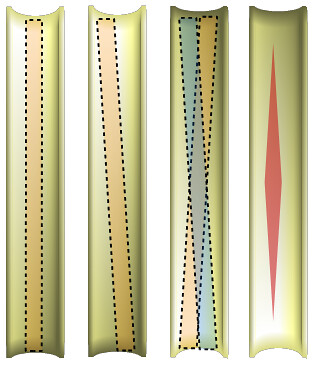

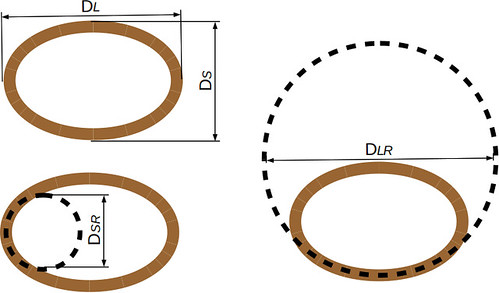

Now comes the time to actually use the gouging machine. Again, a few principles for the adjustment. I don’t know if this is justified with any scientific theory or even practical experience, but intuitively, we want any end-to-end line on the cane to have exactly the same thickness.  Therefore, of extreme importance is complete parallelism of the bed in comparison with the arm that the plane glides on. If there is a vertical discrepancy, either the ends or the middle of the cane will be too thin compared to the overall length at that point…. The middle getting thinner should be impossible regardless of which direction the guide or bed might be slanting. But this has happened to me a lot. Maybe my guide that has a curve in it… very possible.

Therefore, of extreme importance is complete parallelism of the bed in comparison with the arm that the plane glides on. If there is a vertical discrepancy, either the ends or the middle of the cane will be too thin compared to the overall length at that point…. The middle getting thinner should be impossible regardless of which direction the guide or bed might be slanting. But this has happened to me a lot. Maybe my guide that has a curve in it… very possible. Horizontal (sideways) angles, no matter how small, means that the center thick part will not stay centered. In theory, this should actually produce a diamond-shape thick part, but in practice… again, maybe the beaten-up condition of my machine. For years, without realizing it, my machine was unable to do anything else than this because little holes in the bottom of the bed were drilled by adjustment screws tightened too tightly! No matter how I pushed or pulled with the side adjuster screws, the under screws would pull the bed back in the exact same position by sliding back in the holes.

Horizontal (sideways) angles, no matter how small, means that the center thick part will not stay centered. In theory, this should actually produce a diamond-shape thick part, but in practice… again, maybe the beaten-up condition of my machine. For years, without realizing it, my machine was unable to do anything else than this because little holes in the bottom of the bed were drilled by adjustment screws tightened too tightly! No matter how I pushed or pulled with the side adjuster screws, the under screws would pull the bed back in the exact same position by sliding back in the holes.

I fixed this by filing down a flat surface for the screws with a “Dremmel tool”, but most people would criticize (correctly too) that this risks the introduction other imprecisions.

Fitting the cane: chopping length.

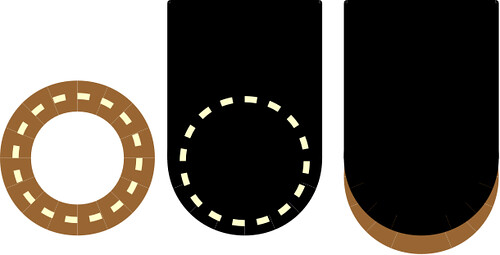

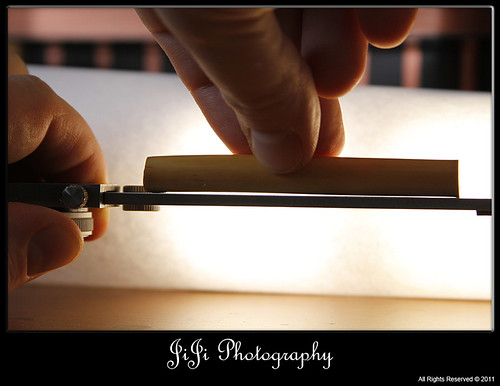

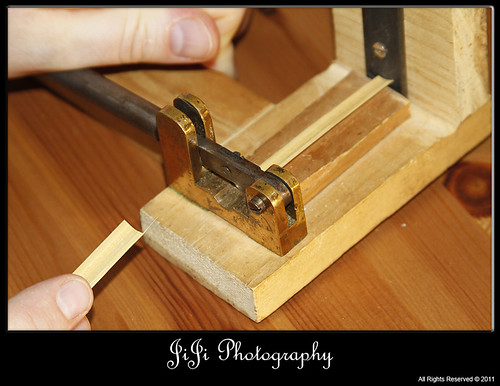

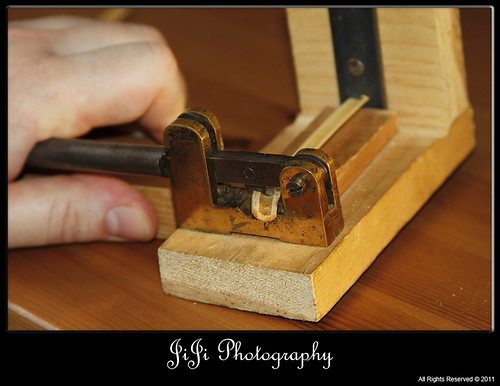

This is so simple, I don’t know why I mention it. The chopping length has one purpose alone: to make the cane fit in the gouging machine. If you use an easel to score the cane before folding, and this easel is of a different length than your gouger bed, TOO BAD: it’s the gouger that matters! On either end of the bed are usually little plates to hold the cane in place: the spring-mounted hook “pinchers” actually do very little but prevent the cane from sliding above those end-plates. Because the plane glides past these plates, to let the blade can cut the entire cane length, there must be curved holes in them to allow free movement without damaging the blade or the plane bottom itself: the bottom helps hold down the cane to prevent ripping and lifting off the bed.

This is so simple, I don’t know why I mention it. The chopping length has one purpose alone: to make the cane fit in the gouging machine. If you use an easel to score the cane before folding, and this easel is of a different length than your gouger bed, TOO BAD: it’s the gouger that matters! On either end of the bed are usually little plates to hold the cane in place: the spring-mounted hook “pinchers” actually do very little but prevent the cane from sliding above those end-plates. Because the plane glides past these plates, to let the blade can cut the entire cane length, there must be curved holes in them to allow free movement without damaging the blade or the plane bottom itself: the bottom helps hold down the cane to prevent ripping and lifting off the bed.

The cane can be a little shorter (up to 1.5mm), but the less snugly it fits, the more risk there is of snagging in the blade and being pulled over the end plates. My machine only has one end plate: I don’t care about the one in back (right side) because it was too difficult to get the right curve on it to prevent damaging the plane and the blade. The one in front (left side) is the only one that really matters, when we’re careful, because it’s the one that keeps the cane in place while cutting.

Shaving Thickness: cut vs. rip.

Shaving Thickness: cut vs. rip.

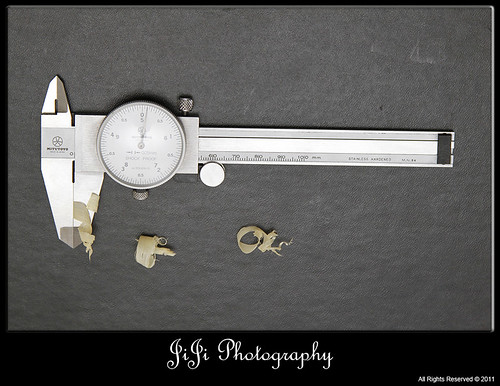

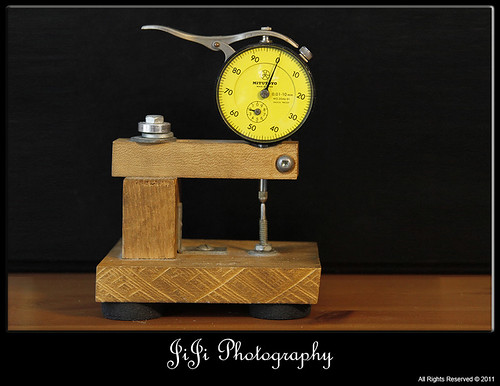

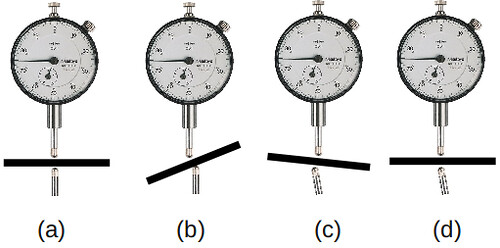

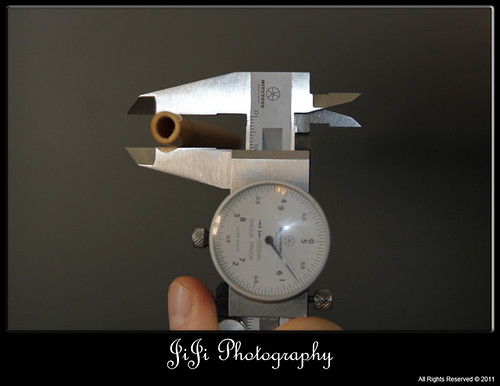

Pretty much all sources of information I have been able to find agree that the cane shavings must measure between 0.05mm and 0.1mm. Thinner than that simply does not cut enough: not only will it take a very long time to gouge (risking compression of the cane), but it just might not cut, period. More than that seems to rip the grains rather than cut them. This is significant because if grains are pulled or torn from each other, then the cane lacks its living properties; it does not “hold together” and all kinds of strange issues happen with the finished reeds.

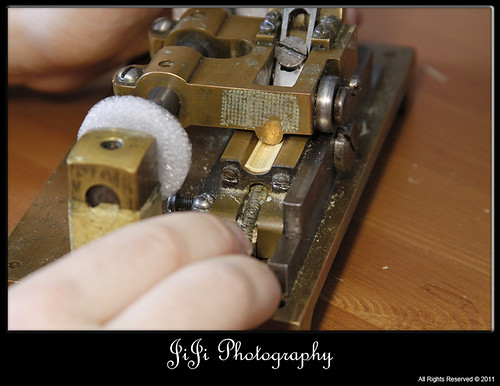

This “video” is a bunch of still images taken at short interval. I flip the cane around every now and then because the blade stops cutting in that direction: I start the blade a little bit inside the cane, so the back always remains a bit thicker until the gouge is complete. The gouge is complete when the roller starts rolling: having reached the guide, there’s nowhere for the blade left to go. Towards the end, notice hat the cane came off the bed a little bit: this is because the cane is a bit concave (curving inward). This piece did not break and I was able to finish it nicely. The shavings change in thickness and appearance. Towards the end, it becomes barely more than dust. At that point I very carefully flip a few more times: even if the roller is rolling, there are often little bumps left over from some degree of ripping.

Grains: good and sponge-cane – a sharp gouger blade.

This is the last point on cane selection. There exist density testers for metals, hard woods, ceramics, polymers and so on. I don’t know how effective they are for cane. For myself, I roll the inside of cane on my thumbnail: if it feels smooth, it’s excellent cane (densely packed grains). There are varying degrees of soft cane and I usually don’t like them. One kind of cane I call “sponge cane” because when scraping the bark, the under part looks porous like a sponge. This is usually horrible and not worth scraping at all.

It’s actually hard to predict while gouging because a rough thumbnail roll is similar for both soft and spongy cane. Also, to really emphasize and clearly identify good, medium and soft canes, the gouger blade must be very sharp. I use the same techniques as I do on my reed knives, but with even better honing stones. Some oboists talk about leaving burrs on their knives…. aye-aye-aye-chihuahua!!! Burrs tear, they don’t cut! But getting rid of them requires great stones and a hard metal blade (always the case with gougers).

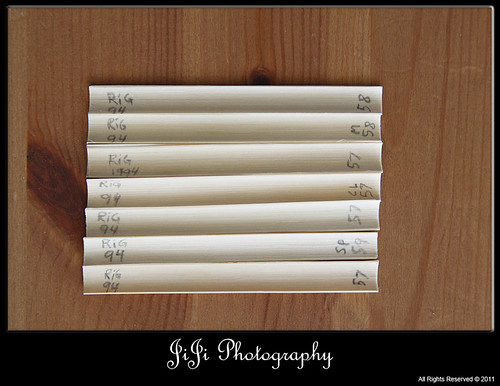

All in all, I actually have had a couple of amazing practice (not concert) reeds with sponge cane. So, again, I don’t throw much away anymore. I use coloured thread with bands of other colours to identify which reed is which and I log in a book the variables (thickness, cane quality, shaper used etc.) associated with each colour combination.

Once the machine is calibrated, no more need to measure, right? – WRONG!

The density and health factors of the cane will change the actual final thickness of the cane. This means that:- the machine can be made of the best metals: this ensures tolerances of 0.01mm or less

- cutting other metals, polymers, ceramics and glass would confirm these tolerances

- cane is a plant (soft, not actually wood) and some degree of compression, “bounce-back” and ripping will occur.

I have not compiled any statistics (variance extremes and standard deviation), but as much as 0.08mm variation has been observed….. due to the beaten-up condition of my very old brass machine that does not even use ball-bearings? Perhaps, but the following observations should hold true on even the best of machines:

- The hardest (densest) cane seems to gouge the thinnest, but not always.

- The softest, spongiest cane tends to resist thinning due to “bounce-back”. It absorbs most downward pressure from the plane and seems to decompress afterwards. End result, less effective cutting.

- Sunny days tend to gouge thinner than cloudy/rainy days.

Theoretically, gouging wet means the thickness measurement should reduce as cane dries and shrinks. This does not matter as long as measurements are always taken in the same state (wet or dry). And people have been reported to like their cane with thicknesses ranging from 0.42mm to 0.68mm, so the important thing is that each oboist determine her/his preference and go from there.

Well, she’s not really unknown because she did study under Heinz Holliger, she did a decent number of recordings including at least one with H.H. and I believe she is a teacher and orchestral oboist in Switzerland… but I don’t know where and Google is not very helpful in getting information on her.

Well, she’s not really unknown because she did study under Heinz Holliger, she did a decent number of recordings including at least one with H.H. and I believe she is a teacher and orchestral oboist in Switzerland… but I don’t know where and Google is not very helpful in getting information on her.